Bearing Friction

A bearing is the machine element used to support a rotating shaft. Bearing friction is the friction that exists between the rotating shaft and bearing that is supporting that shaft. Though many types of bearings exist (plain, ball, roller, hydrodynamic) in this course we will only be looking at plain bearings (also sometimes called journal bearings).

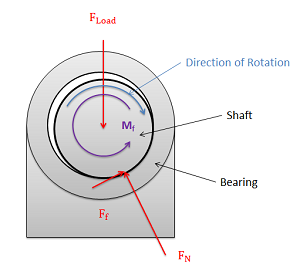

A plain bearing consists of a circular shaft fitted into a slightly larger circular hole as shown to the right. The shaft will usually be rotating and will be exerting some sort of load (F load) onto the bearing. The bearing will then be supporting the shaft with some normal force and a friction force will exist between the bearing surface and the surface of the shaft. Sometimes the rotation of the bearing will cause the shaft to climb up the side of the bearing, causing the angle of the normal and friction forces to change, but this climbing is usually small enough that it is neglected.

If we assume that the climbing in the bearing is negligible, the normal of the bearing on the shaft will be equal and opposite to loading force of the shaft on the bearing. Furthermore, if the shaft is rotating relative to the bearing, then the friction force will be equal to kinetic coefficient of friction times the normal force of the bearing on the shaft.

If the climb angle is assumed to be small, then...

| \[F_{load}=F_{N}\] |

| \[F_{f}=\mu _{k}* F_{N}\] |

The friction force will then be exerting a moment about the center of the shaft opposing the rotation of the shaft. Unless some other moment is keeping the shaft spinning, this moment will eventually slow down and stop the rotation in the shaft. The magnitude of this moment will be equal to the magnitude of the friction force times the radius of the shaft.

| \[M_{f}=r_{shaft}* \left( \mu _k* F_{N} \right)\] |

Another important factor to keep in mind is that most bearings are lubricated. This can significantly lower the coefficients of friction (this the the main reason for using lubrication actually). When performing calculations, it is import to know if the bearing is lubricated and if so using an appropriate friction coefficients.