Work, Kinetic Energy, and Potential Energy

The concepts of Work and Energy provide the basis for solving a variety of kinetics problems, and an alternative to the force, mass, and acceleration method presented in the previous chapter. Generally, this method is called the Principle of Work and Energy, and it can be boiled down to the idea that the work done to a body will be equal to the change in energy of that body. Dividing energy into kinetic and potential energy pieces as we often do in dynamics problems, we arrive at the following base equation for the conservation of energy.

| \[W=\Delta KE + \Delta PE\] |

Before jumping into the application of this method though, it is important to first define the three terms used in the equation, the ideas of work, kinetic energy, and potential energy.

Work:

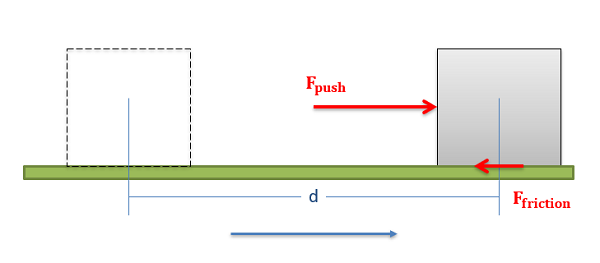

Work in general is a force exerted over a distance. If we imagine a single, constant force pushing a body in a single direction over some distance, the work done by that force would be equal to the magnitude of that force times the distance the body traveled. If we have a force that is opposing the travel (such as friction) it would be negative work.

| \[W_{push}=F_{push}*d\] |

| \[W_{friction}=-F_{friction}*d\] |

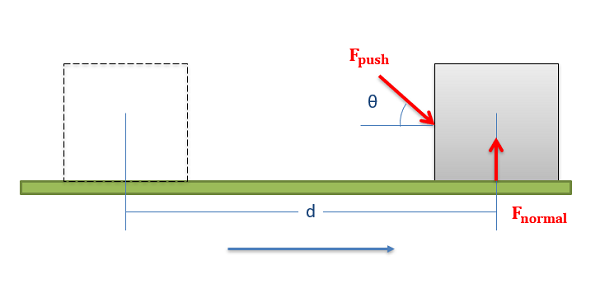

For instances where forces and the direction of travel do not match, the component of the force in the direction of travel is the only piece of the force that will do work. Following through with this logic, forces that are perpendicular to the direction of travel for a body will exert no work on a body because there is no component of the force in the direction of travel.

| \[W_{push}=F_{push}cos(\theta)*d\] |

| \[W_{normal}=0\] |

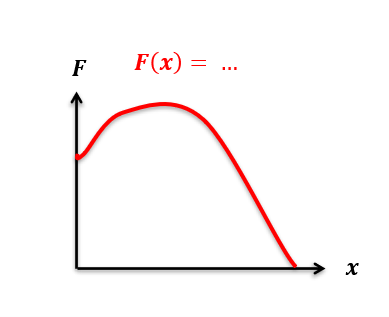

Finally, in the case of a force that does not have a constant magnitude, we will need to account for the changing magnitude of the force over the distance traveled. To do this we will simply integrate the force function over the distance traveled by the body. Just as before, only the component of the force in the direction of travel will count towards the work done and forces opposing travel will be negative work.

| \[W=\int_{x1}^{x2} F(x) dx\] |

Kinetic Energy:

Kinetic energy is the the energy of mass in motion, and for a particle or translational system (with no rotation) it will be equal to one half of the mass of the body times the velocity of the body squared.

| \[KE=\frac{1}{2}mv^{2}\] |

If we wish to determine the change in kinetic energy (as is used in the work and energy equation), we would simply take the final kinetic energy minus the initial kinetic energy.

| \[\Delta KE=\frac{1}{2}mv_{f}^{2}-\frac{1}{2}mv_{i}^{2}\] |

As a note, even though the velocity of a body has a direction, kinetic energy does not have a direction.

Potential Energy

Potential energy, unlike kinetic energy, is not really energy at all. Instead, it represents the work that a given force will potentially do between two instances in time. Potential energy can come in many forms, but the two we will discuss here are gravitational potential energy, and elastic potential energy. As the names imply, gravitational potential energy represents the potential work that the gravitational force will do, while elastic potential energy represents the potential work a spring force will do. We often use these potential energy terms in place of the work done by gravity or springs because it will simplify the math. It is important to note that when we include these potential energy terms, we should not also include the work done by gravity or spring forces as well, as this would double count those forces.

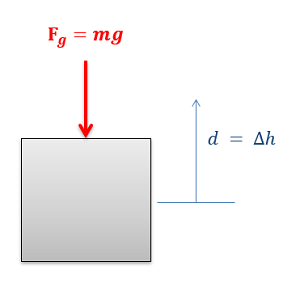

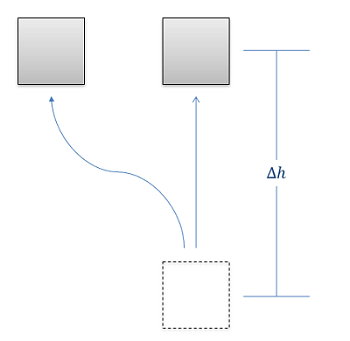

Gravitational Potential Energy

If we were to examine the work done by gravity as we lift the an object up by some change in height, we would see that it is equal to the negative of force times distance, because the gravity opposes the upwards displacement. In this case the magnitude of the force is equal to the mass times the acceleration due to gravity g (9.81 m/s2 or 32.2 ft/s2 on the earth's surface) while the distance is the change in height.

| \[W_{gravity}=-m*g*\Delta h\] |

When changing this from a work term to an energy term, we will move the term from one side of the work and energy equation to the other. When we do this, we will wind up converting the negative work value into a positive energy value. Moving the body upwards represents a positive change in gravitational potential energy, while moving the body downwards represents a negative change in gravitational potential energy. In equation form, this is as follows.

| \[\Delta PE_{gravity}=m*g*\Delta h\] |

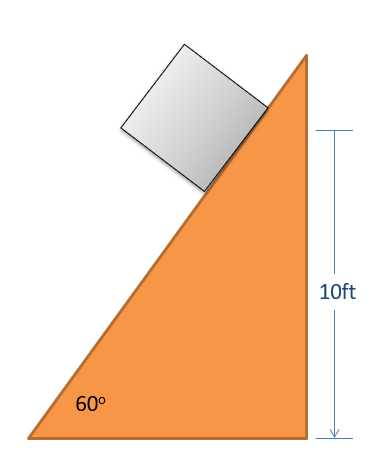

It is important to note that the change in height here is the not the total distance traveled, but only the vertical displacement between the starting and ending states. When working with US customary systems, it is also important to remember that the weight of an object is not equal to the mass. Instead the weight (in pounds) is the mass times g already. This means that the change in gravitational energy is equal to the weight time the change in height.

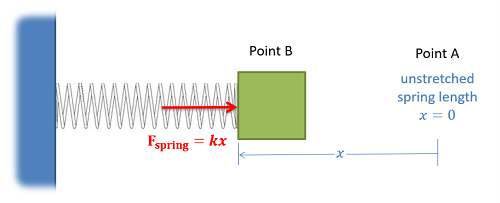

Elastic Potential Energy

Elastic potential energy represents the potential work done by a spring that is stretched or compressed as it returns to its natural, unstretched length. The force a spring exerts is linearly related to the amount of stretch itself by the spring constant k, where the spring force is equal to the spring constant (k) times the distance the spring is stretched or compressed (x) beyond its natural, unstretched length. The spring force will always push or pull the object back towards the unstretched length of the spring.

To find the work done by a spring as we compress it from its unstretched length (point A) to some other point (Point B), we simply need to integrate the spring force over this distance. As this is the integral of a simple linear relationship that opposes the displacement we wind up finding that the work done by the spring is equal to negative one half times the spring constant (k) times the amount of stretch (x) squared.

| \[W_{spring}= \int_{0}^{x}(kx)dx=-\frac{1}{2}kx^{2}\] |

Rather than leaving this as work, we will instead move it to the energy side of the work and energy equation. In doing so, we will drop the negative sign from our value.

| \[PE_{spring}=\frac{1}{2}kx^{2}\] |

In the equation above, the stiffness of the spring (k) represents the amount of force the spring exerts per unit distance it is compressed. A stiffer spring, with a higher value of k, will be harder to stretch or compress, while a less stiff spring, with a lower value of k, will be easier to stretch or compress. Spring manufacturers may specify the k value, though this can also be determined experimentally by stretching or compressing a spring a set amount and measuring the force exerted by the spring at that set displacement.

It's also important to remember that in the equation above, x is not the length of the spring but instead the distance the spring has been stretched or compressed beyond its unstretched length. For example, a spring that is naturally 10 cm long has no elastic potential energy when it is just sitting there unstretched at 10 cm long.

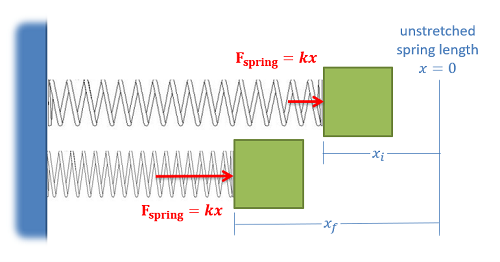

To find the change in elastic potential energy (Delta PE), as is used in the work and energy equation, we simply take the final elastic potential energy minus the initial elastic potential energy.

| \[\Delta PE_{spring}=\frac{1}{2}kx_{f}^{2}-\frac{1}{2}kx_{i}^{2}\] |

In this case, it is important to remember that the amount of stretch (x final or x initial) is always measured relative to the unstretched length of the spring. We cannot simply use a change in length of the spring, as this will give you invalid results.