Relative Motion Analysis (Scalar)

Relative motion analysis is one method used to analyze bodies undergoing general planar motion. General planar motion is motion where bodies can both translate and rotate at the same time. Besides relative motion analysis, the alternative is absolute motion analysis. Either method can be used for any general planar motion problem, however one method may be significantly easier to apply in certain situations.

Absolute motion analysis will require calculus and is generally faster for simple problems and problems where only the velocities (and not accelerations) are required. Relative motion analysis will not require calculus, but does necessitate using multiple coordinate systems and is generally easier to use for more complex problems and problems where velocities and accelerations are being analyzed.

Utilizing Relative Motion Analysis

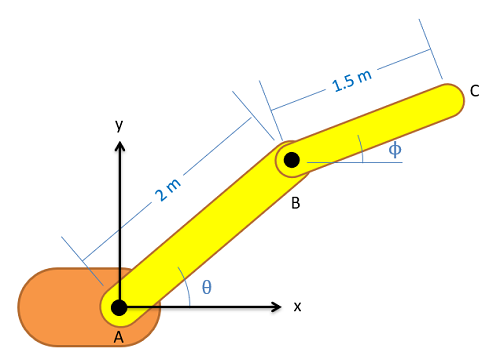

To start our discussion on relative motion analysis, we are going to imagine a simple robotic arm such as the one below. In this arm, we have a two arm sections of fixed length with motors causing rotations at joint A and joint B.

The first step in relative motion analysis is to break the motion down into simple steps and assign a coordinate system (with r and theta directions) to each step in the chain of motion. We will always start at a fixed point and move step by step from there. In the case of our robotic arm, Joint A is the only point that will not be moving so we start there and we have two cases of rotation without extension as we move from A to B then B to C.

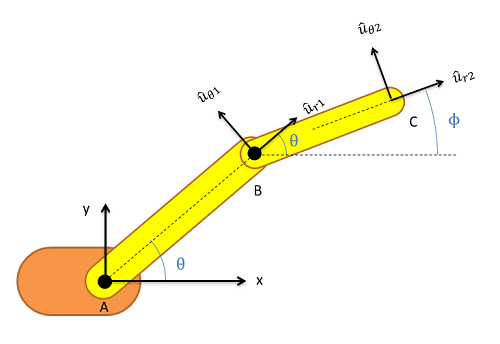

To since there are two steps to the motion there will be two coordinate systems. The first coordinate system will be attached to member AB, with the r direction going from point A to point B. The theta direction will then be ninety degrees counterclockwise from the r direction. The second coordinate system will be attached to member BC, with the r direction going from point B to point C. Again, the theta direction is ninety degrees counterclockwise from the r direction. At this point it is usually good to identify the angles of each of the r and theta directions with respect to ground. Below is a picture of the robotic arm with both coordinate systems drawn in.

For relative motion analysis, we can identify the velocity or acceleration of the end point of the arm (C) with respect to the ground (A) by finding the velocity acceleration of B with respect to A and adding the velocity or acceleration of C with respect to B, just as we did with particles.

| Velocity: | \[\vec{v}_{C/A}=\vec{v}_{B/A}+\vec{v}_{C/B}\] |

|---|---|

| Acceleration: | \[\vec{a}_{C/A}=\vec{a}_{B/A}+\vec{a}_{C/B}\] |

The relative motion analysis equations above are for a two-part motion (there are two sections to the arm in our example) but we can easily expand the above equation into three, four, or even more pieces for more complex mechanisms by adding more steps to the left side of our equation.

To use the above equations, we will need to plug in the information we know. Plugging in velocities or accelerations that are given as part of the problem for any particular points is a good place to start. If the velocity of points B or C were given for example, we would plug that in for vB/A or vC/A respectively. Do remember that point A is our fixed ground point so vC/A is the velocity of point C relative to the ground, while vC/B is the velocity of point C with respect to point B. If any point is fixed (other than our original ground point, which will always be fixed) we can also plug in zeros for both velocity and acceleration of that point. Do remember the above equation is a vector equation, so these velocities have both a magnitude and a direction.

To take into account rotation or extension of any individual pieces, we will need to look back to our kinematics equations for polar coordinator systems. Below are the equations we had for velocity and acceleration.

| Velocity: | \[v=\dot{r}\hat{u}_{r}+r\dot{\Theta}\hat{u}_{\Theta}\] |

|---|---|

| Acceleration: | \[a=(\ddot{r}-r\dot{\Theta}^{2})\hat{u}_{r}+(2\dot{r}\dot{\Theta}+r\ddot{\Theta})\hat{u}_{\Theta}\] |

In the above equations, r represents the length of the respective arm piece (the length of member AB or BC), r dot represents the rate at which that length is increasing, and r double dot represents the rate at which that rate is increasing. The theta term represents current angle of the arm piece, theta dot is the angular velocity of that arm piece, and theta double dot is the angular acceleration of that arm piece. The ur and utheta directions are the r and theta directions that are attached to that particular section of the arm (in our earlier drawing ur1 and utheta1 were attached to member AB and ur2 and utheta2 were attached to member BC).

Though it's certainly possible to have a mechanism that is rotating and extending at the same time, we will often have either just simple rotation, or just simple extension along a fixed direction. With simple rotation, the r dot and r double dot terms are zero, and our equations reduce down to the following.

| Velocity: | \[v=r\dot{\Theta}\hat{u}_{\Theta}\] |

|---|---|

| Acceleration: | \[a=-r\dot{\Theta}^{2}\hat{u}_{r}+r\ddot{\Theta}\hat{u}_{\Theta}\] |

If we have simple extension, where the length of the piece is changing but there is no rotation, the theta dot and theta double dot terms would be zero and our original equations would reduce down to the following.

| Velocity: | \[v=\dot{r}\hat{u}_{r}\] |

|---|---|

| Acceleration: | \[a=\ddot{r}\hat{u}_{r}\] |

If we use the appropriate set of equations for the type of motion in each step and plug in known quantities for angular velocities, angular accelerations, and rates or extension for each piece, we can add these pieces to our relative motion analysis equation from earlier. Again these are vectors so be sure to indicate both the magnitudes and directions when we put them into the equation.

Once we have everything in our vector equation, we will break the vector equation into x and y components in order to solve for any unknowns. Simply find the angles or each of the r and theta directions using your diagram and use sines and cosines to break the individual vectors down into x and y components. Once you have everything in component form, you should be able to solve for any unknowns in your equations. As a note, it is often necessary to start with the velocity equations and solve for some unknowns there before moving on to the acceleration equations.