The Mass Moment of Inertia

The Mass Moment of Inertia represents a body's resistance to angular accelerations about an axis, just as mass represents a body's resistance to linear accelerations. This is represented in an equation with the rotational version of Newton's Second Law.

| \[F=m a\] |

| \[M=I \alpha\] |

Just as with Area Moments of Inertia, the mass moment of inertia can be calculated via moment integrals or via the method of composite parts and the parallel axis theorem. This page will only discuss the integration method, as the method of composite parts is discussed on a separate page.

The Mass Moment of Inertia and Angular Accelerations

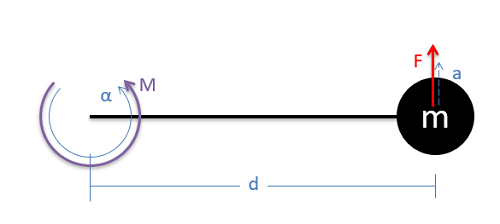

The mass moment of inertia is a moment integral, specifically the second, polar, mass moment integral. To see why this relates moments and angular accelerations, we start by examining a point mass on the end of a massless stick as shown below. Imagine we want to rotate the stick about the left end by applying a moment there. We want to relate the moment exerted to the angular acceleration of the stick about this point.

To relate the moment and the angular acceleration, we need to start with the traditional form of Newton's Second Law, stating that the force exerted on the point mass by the stick will be equal to the mass times the acceleration of the point mass (F = m a). In this case the moment will be related to the force in that the force exerted on the mass times the length of the stick (d) is equal to the moment. We can also relate the linear acceleration of the mass in that the linear acceleration is the angular acceleration times the length of the rod (d). If we take these two substitutions and put them into the original F = m a equation, we can wind up with an equation that relates the moment and the angular acceleration for our scenario. A simplified version of this new relationship states that the moment will be equal to the mass times the distance squared times the angular acceleration. This mass times distance squared term (relating the moment and angular acceleration) forms the basis for the mass moment of inertia.

| \[F=m*a\] | |

| \[M=F*d\] | \[a=d*\alpha\] |

| \[M=(m*d^2)*\alpha\] | |

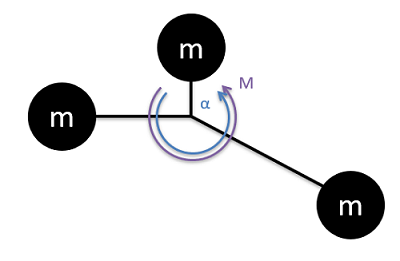

Taking our situation one step further, if we were to have multiple masses all connected to a central point, the moment and angular acceleration would be related by the sum of all the mass times distance squared terms.

| \[M=\sum (m*d^2)*\alpha\] |

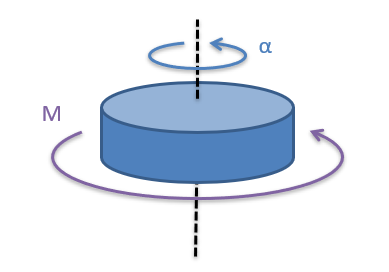

Taking the final step, rigid bodies with mass distributed over a volume are like an infinite number of small masses about an axis of rotation. Rather than the massless sticks holding everything in place, the mass is simply held in place by the material around it. To relate the moment and angular acceleration in this case, we use integration to add up the infinite number of small mass times distance squared terms.

| \[M=\int_{m} (dm*d^2)*\alpha\] |

This moment integral can be calculated for any given shape, called the mass moment of inertia, relates the moment and the angular acceleration for the body about a set axis of rotation.

| \[I=\int_{m} (dm*d^2)\] |

Calculating the Mass Moment of Inertia via Integration

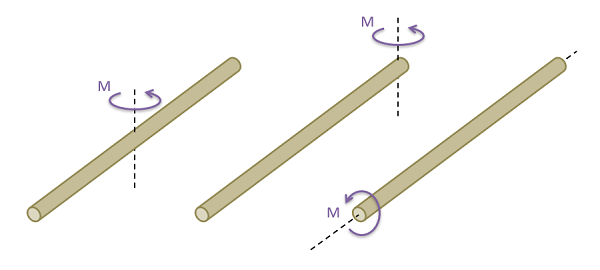

The first step in calculating the mass moment of inertia is to determine the axis of rotation you will be using. Unlike mass, the mass moment of inertia is dependent upon for the point and axis that we are rotating about. We can easily demonstrate this with something like a broomstick, where depending on the position and the direction of the axis we are rotating about, it can be more or less difficult to rotate the broomstick.

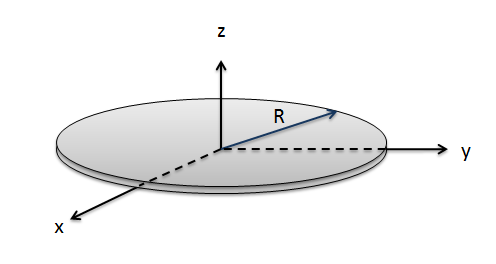

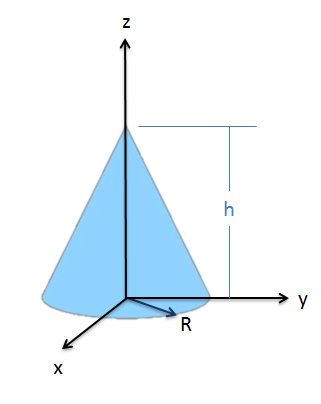

After choosing the axis of rotation, it is helpful to draw the shape with the axis of rotation included. This is a polar integral, so we will be taking the mass integral radiating outwards from this axis of rotation.

Also, We are integrating over the mass, and the mass at any given point will be the density times the volume. If the object we are examining has a uniform density, as is often the case, we can pull that density constant outside of the integral, leaving a integral of the volume reaming. Density is rarely given in these instances, but if you can determine the overall mass and overall volume you can use that as well. If we put all of this into the original equation we had above we wind up with the following.

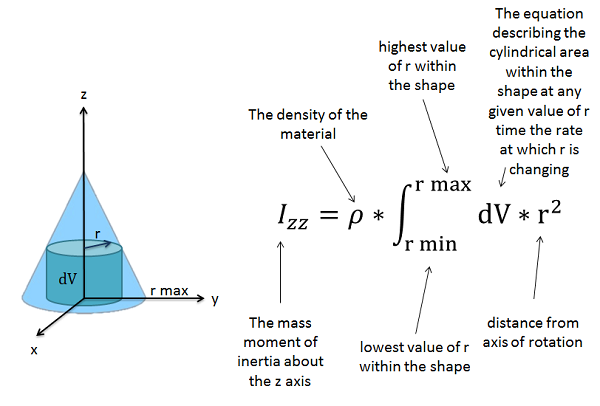

| \[I=\rho*\int_{rmin}^{rmax} (dV*r^2)=\frac{m}{V}*\int_{rmin}^{rmax} (dV*r^2)\] |

For the polar integral, we need to define dV in terms of a radius (r) moving outwards from the axis of rotation. The rate of change of the volume (dV) will be the cylindrical surface area at a given radius times rate at which that radius is increasing (dr). The height, radius, and holes in this cylindrical surface may all be changing so this dV term may become quite complex, but technically we could find this for mathematical function for any shape. Once we have the dV function in terms of r, we multiply that function by r squared and we will evaluate the integral.