The Equations of Motion with Normal-Tangential Coordinates

Continuing our discussion of kinetics in two dimensions we can examine Newton's Second Law as applied to the normal-tangential coordinate system. In its basic form, Newton's Second Law states that the sum of the forces on a body will be equal to mass of that body times the rate of acceleration. For bodies in motion, we can write this relationship out as the equation of motion.

| \[\sum \vec{F}=m*\vec{a}\] |

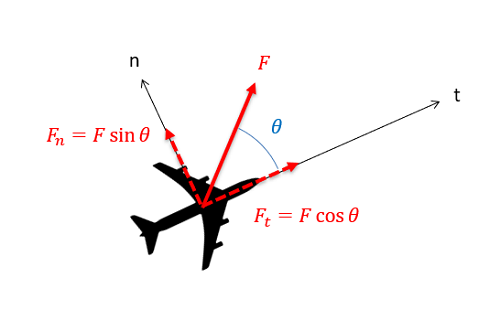

Just as we did with with rectangular coordinates, we will break this single vector equation into two separate scalar equations. This involves identifying the normal and tangential directions and then using sines and cosines to break the given forces and accelerations down into components in those directions.

| \[\sum F_{n}=m*a_{n}\] |

| \[\sum F_{t}=m*a_{t}\] |

Just as with a the rectangular coordinates, the equations of motion are often used in conjunction with the kinematics equations, which relate positions, velocities and accelerations as discussed in the previous chapter. In particular, we will often substitute the known values below for the normal and tangential components for acceleration.

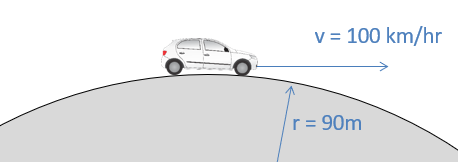

| \[a_{n}=v*\dot{\Theta}=\frac{v^2}{\rho}\] |

| \[a_{t}=\dot{v}\] |

Normal tangential coordinates can be used in any kinetics problem, however they work best with problems where forces maintain a consistent direction relative to some body in motion. Vehicles in motion are a good example of this where the direction of the forces applied are largely dependent on the current direction of the vehicle, and these forces will rotate with the vehicle as it turns.